Gwangju, city of light and courage

Gwangju is a large, vibrant, and generous city where past and present intersect at every street corner.

Beneath its apparent modernity lies an indelible memory: that of two uprisings that forever marked Korean history.

In the 1920s, Gwangju rose up against Japanese rule.

And in May 1980, its people rose up again—this time for freedom and democracy.

These events, engraved in stone and in hearts, have made Gwangju a symbol of collective courage and rediscovered dignity.

Today, the city has reinvented itself without ever forgetting.

Its museums, murals, and memorial parks tell the story with modesty and pride.

But Gwangju is also about human warmth, colorful markets, lively cafes, and artistic creativity that pulsates in every street.

A city of light, as its name suggests, Gwangju continues to illuminate the conscience of contemporary Korea.

Walking through its streets, you can feel the quiet strength of a people who have transformed pain into hope and memory into future.

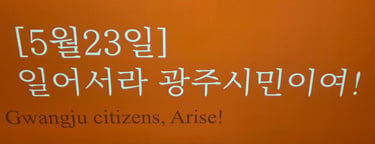

Mémorial du 18 mai

1980 – A Reminder of the Facts :

Forty-five years ago martial law was declared.

In October, President Park Chung-hee was assassinated, leaving a political vacuum. Despite the establishment of a provisional government, power soon fell into the hands of General Chun Doo-hwan. On December 12, 1979, he orchestrated a military coup and seized control of the country, sidelining his rivals.

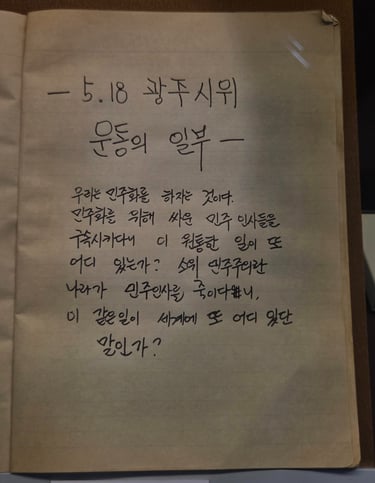

Between March and April 1980, the population rose up, demanding an end to martial law, free elections, and greater democratic freedoms.

The movement spread nationwide, but was most intense in Seoul and Gwangju. The demonstrations prompted the regime to impose even stricter measures, extending martial law to the entire country. Parliament was dissolved, political activities were banned, the press was censored, universities were closed, and many student leaders, trade unionists, and opposition figures were arrested.

It was May 17, 1980.

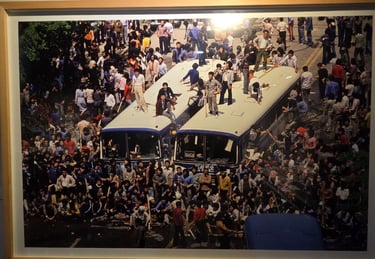

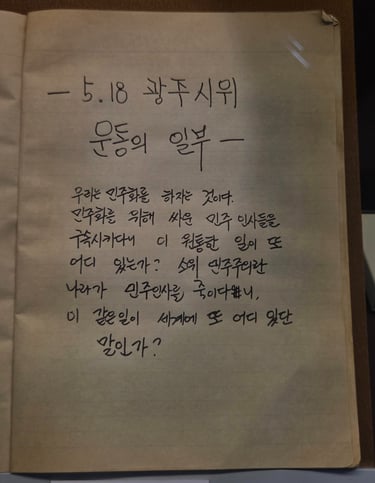

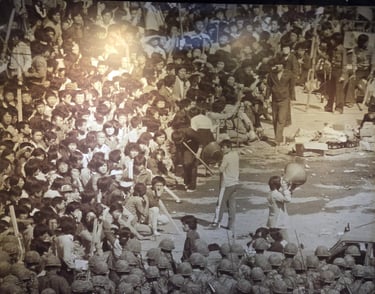

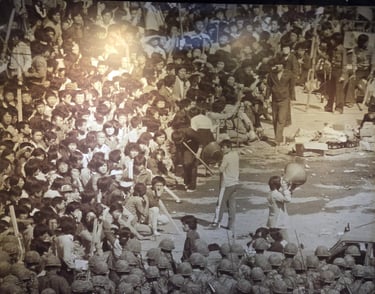

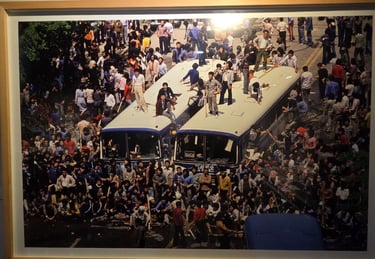

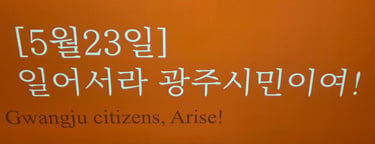

The next day, May 18, students took to the streets. The army was sent in to suppress the uprising. Outrage spread among the citizens, who joined the students, transforming the movement into a full-scale civic insurrection.

The uprising lasted ten days, until May 27, leaving hundreds dead.

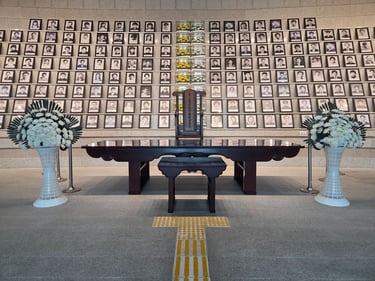

Chunyeommun or Gwangju National Cemetery – A Place of Emotion, Dignity, and Quiet Reflection

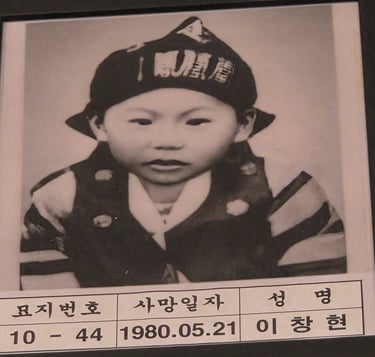

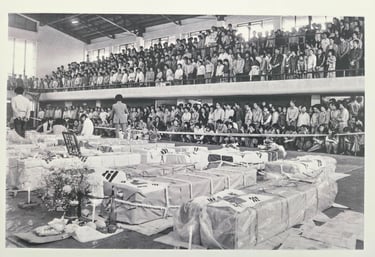

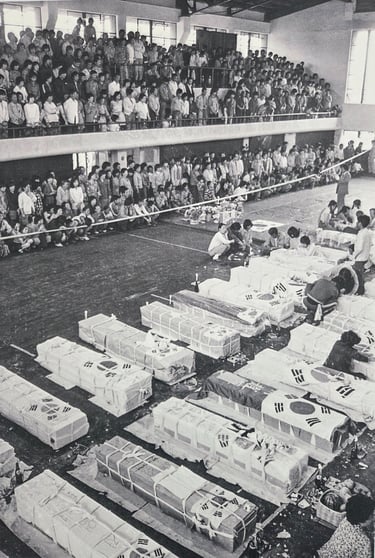

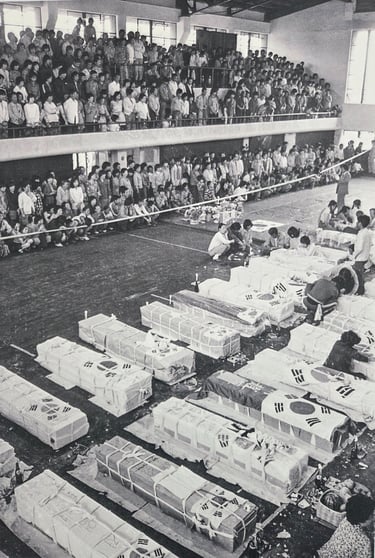

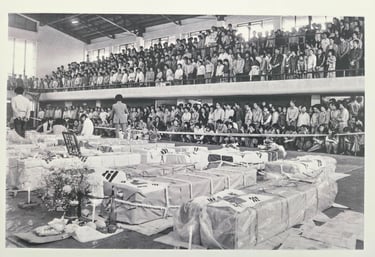

Bodies were collected in carts and sanitation trucks, many buried anonymously in Mangwol-dong Cemetery. For those whose bodies were recovered before the army’s intervention, collective funerals were held, allowing families to grieve and pay their final respects.

In the 1990s, a government commission investigated the tragedy, leading to the creation of a national cemetery to honor the victims’ fight for democracy — Chunyeommun. The remains of those buried at Mangwol-dong were later transferred there.

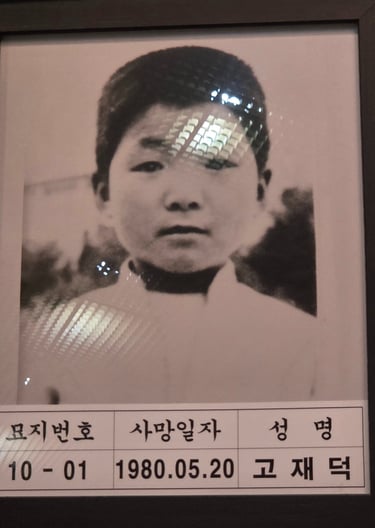

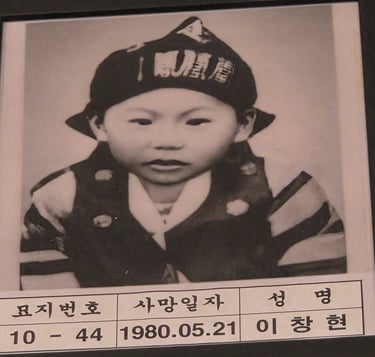

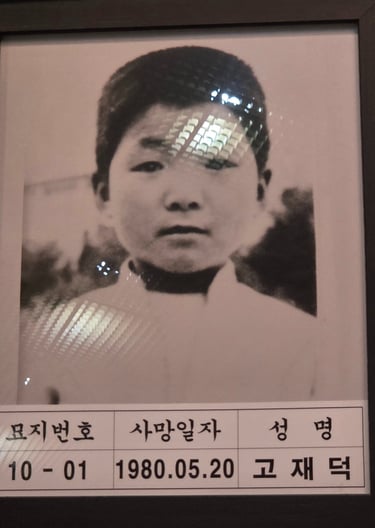

Today, the cemetery holds 746 graves, resting places for those killed during the May 1980 demonstrations, as well as for others who were wounded or later passed away — whether or not they took part directly in the events.

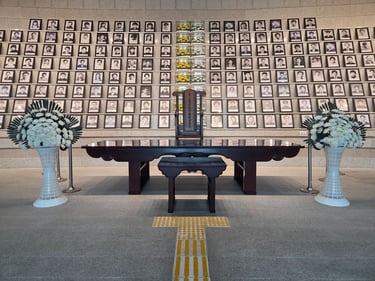

To reach the cemetery, one must pass through the Gate of Democracy, cross the vast Plaza of Democracy, and then arrive at the Gate of Remembrance (Chunyeommun). Beyond it rises the Memorial Tower, four meters high, its two clasped hands symbolizing resurrection and new life. At its base, an altar and incense burners invite visitors to pay tribute to the dead.

As you walk further, large reliefs unfold along the sides, depicting scenes from the uprising. To the right stands a dolmen-shaped monument, echoing traditional Korean tombs. Inside are portraits and memorial tablets of the victims — among them, children and infants. Facing it, the Gate of History displays photographs and documents retracing the days of May.

On both sides, engraved reliefs recount the anger and hope of May 1980.

Every detail, every symbol, guides the visitor through a silent dialogue between pain and perseverance.

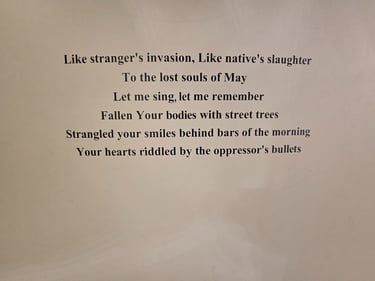

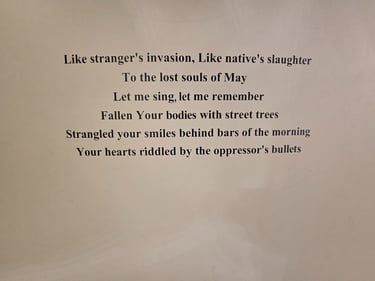

“March for the Beloved”

This is a South Korean protest song, composed in 1981 in memory of Yoon Sang-won, a pro-democracy activist, and Park Ki-soon, a labor activist — both of whom died during the Gwangju Uprising in 1980. Listen to it, and you will feel the power of its words and voices.

Without love, nor honor, nor name,

We swore to fight all our lives.

Our comrades are gone, the flag still flies.

Until the new day comes, we shall not waver.

Time passes, but the land and mountains remember

The burning cries that rose in awakening.

We march ahead — follow us, the living!

We march ahead — follow us, the living!

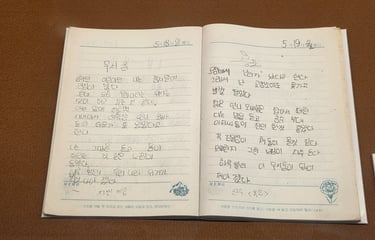

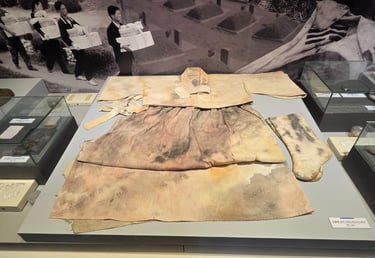

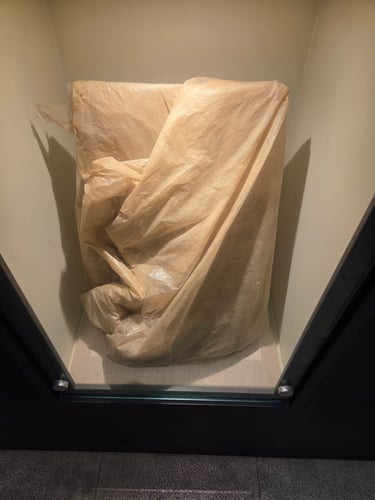

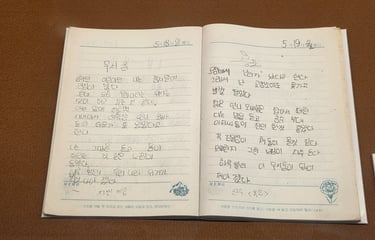

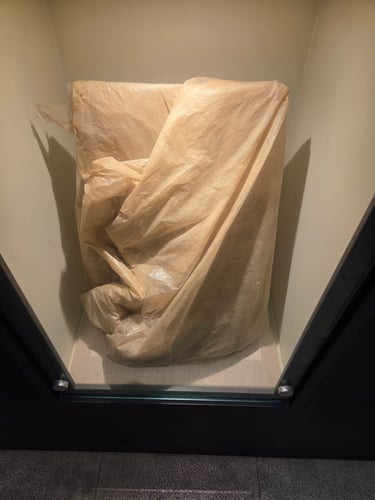

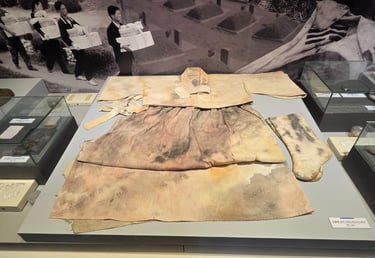

The photos show relics preserved at the May 18 Democratic Uprising Archives: students’ notebooks - a reconstructed scene with shoes scattered after the army assaults - watches recovered from the bodies - the tarps used to wrap the dead - a reconstruction of the mass graves - and a metal lunch box like those used by the women and mothers of protesters to prepare meals during the uprising. Also pictured are the May 18 Democratic Square and a building still bearing the marks of bullet impacts.

I invite you to read “Human Acts by Han Kang, Nobel Prize in Literature 2024 — you will recognize several of the scenes depicted in the photos above.

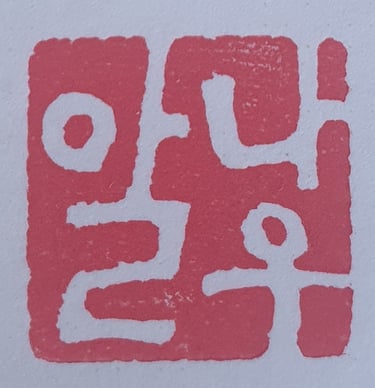

Mémorial du Mouvement des Étudiants de 1929

1929 – A Reminder of the Facts

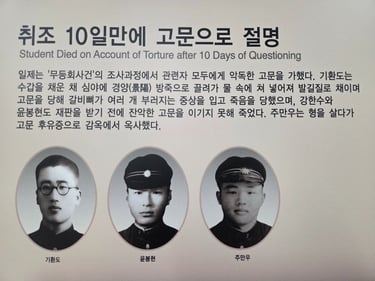

Nearly a century ago, on November 3, 1929, a student movement of unprecedented scale erupted in Gwangju under Japanese colonial rule.

The triggering event seemed trivial: an altercation between Korean and Japanese students at Naju Station. But tension quickly escalated, and Gwangju students began organizing demonstrations against discrimination, colonial oppression, and in defense of national dignity.

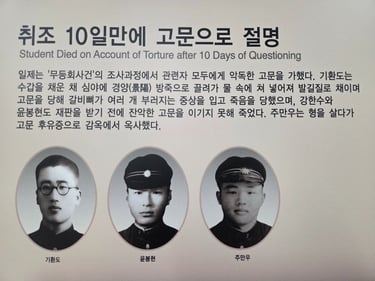

Starting on November 3, thousands of students marched through the streets, soon joined by other schools, other cities, and eventually the general population. The movement rapidly spread across the country, mobilizing more than 50,000 participants. The Japanese authorities responded with harsh repression — mass arrests, imprisonment, and school expulsions. More than 500 students were arrested, dozens were injured, yet the movement left a deep mark on the national consciousness.

This episode is regarded as the second great national mobilization after the March 1st Movement of 1919, and as one of the cornerstones of Korea’s struggle for independence.

Places of Memory

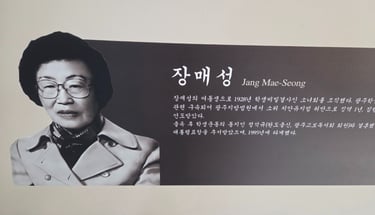

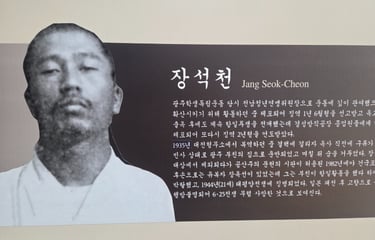

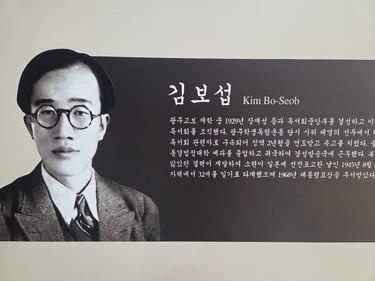

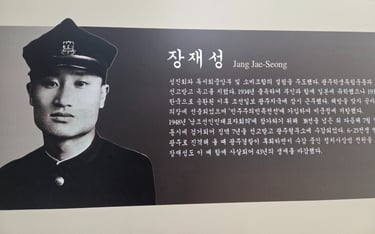

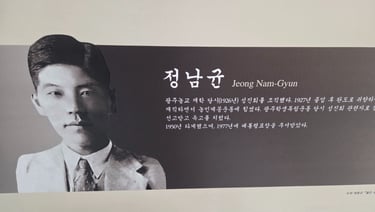

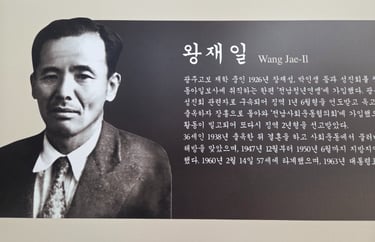

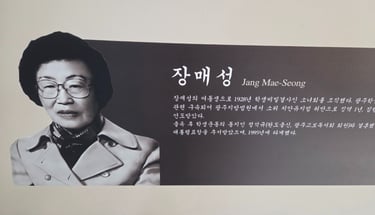

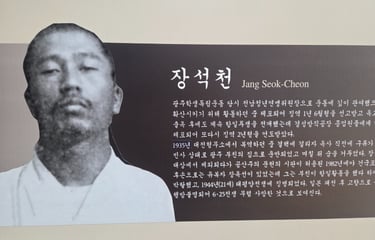

Today in Gwangju, the 1929 Student Movement Memorial preserves this legacy. Located near the former school where the protests were first organized, it honors the courage of the young people who dared to challenge the colonial empire.

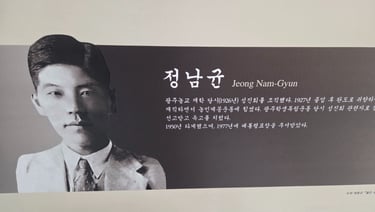

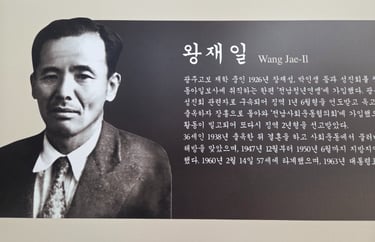

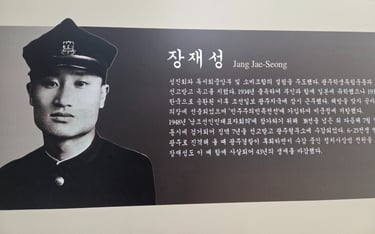

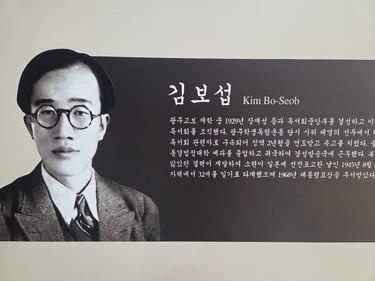

The building, sober and imposing, opens onto a large square where the Korean flag flies proudly. Inside, galleries display original documents, underground newspapers, personal belongings, and photographs of arrested students. A large mural depicts the student marches, flags in hand, confronting Japanese repression.

Outside, a white stone monument stands engraved with the names of the participants. On the plaza, a sculpture of marching students captures their determination — their faces turned toward the future. Nearby, a memorial stele recalls the key sites of the November 1929 mobilization.

Conceived as an educational space, the site hosts annual commemorations and school ceremonies, passing on to younger generations the memory of these teenagers who became enduring symbols of resistance.

Through these two sacred places, the entire modern history of Korea unfolds before our eyes.

"Water of life"

At the heart of the May 18 Memorial in Gwangju, within the underground level of the main building of the May 18 National Cemetery, lies a symbolic installation known as the “Water of Life” or “Source of Democracy.” This source, visible in the photograph, flows along a luminous channel that runs through several sections of the museum, offering a journey that is both aesthetic and commemorative.

Every element of this installation is rich with meaning. The clear and continuous flow of water represents life and purity, while also preserving the memory of the citizens who lost their lives during the May 1980 Uprising. The blue and red lights evoke the duality of tragedy and hope, as well as the cosmic balance of the Taegeuk, the central symbol of the Korean flag. The linear path of the water connects the different parts of the memorial, symbolizing the ongoing continuity of historical memory and democracy within Korean society.

The May 18 Memorial was designed not only to document the events of the Gwangju Uprising but also to commemorate the human dignity and peaceful resistance of its citizens. Water plays a central role in this memorial architecture: present both in the exterior pools of the cemetery and within this interior source, it embodies the idea that democracy — nourished by the sacrifice of human lives — remains living and fluid.

Certain visitor practices further highlight this symbolism. Pouring a few drops into the main basin is a gesture of respect and purification, inspired by traditional Korean rituals. This commemorative custom, far from any religious connotation, reflects how individuals can take part — through a simple, silent act — in keeping collective memory alive.

And finally, the lights of Gwangju